Compositional Inequality

In this section, my goal is to provide a straightforward and intuitive explanation of the concept of compositional inequality (CI). I will begin with an illustrative example, followed by a more formal definition of compositional inequality. I will then introduce a "Case Studies" section to gather all relevant works related to CI. Lastly, I will discuss a few normative implications of compositional equality. You can also delve deeper into the topic of compositional inequality by reading my recent paper on this research agenda, or checking out my blog post for the Stone Centre at UCL, listening to my conversation with Mark Fabian, or reviewing my inequality module (lectures 8 and 9).

Illustrative Example

Imagine an economy consisting of two individuals, Peter and Rachel. Peter's monthly income is $1,000, while Rachel's is $10,000. In this economy, there exists income inequality, as illustrated by a convex Lorenz curve rather than a flat one.

Let's consider not only the income levels of Peter and Rachel but also the source of their income, which can be categorized as either capital (K) or labor (W) income. Rachel derives all her income from capital sources, amounting to $10,000. This income is generated through her ownership of company shares, monthly rental income, and investments in government bonds. Meanwhile, Peter earns $1,000 in labor income, working as a bartender in London.

However, it's worth noting that Rachel could also earn $10,000 in labor income instead of capital income, while Peter could earn $1,000 in capital income. In this alternative scenario, Rachel might be employed by an investment fund or work for an international organization, while Peter could be receiving a monthly rental income. Now, let's transition to another extreme scenario, as illustrated in the figure below.

Rachel and Peter could also have an equal composition of capital (20%) and labor (80%) income in their total income. This means that, even though the overall level of income inequality persists (with Rachel earning $10,000 per month and Peter earning $1,000), the income composition is identical across the population, which, in this example, consists of only two individuals. Therefore, both Rachel and Peter have a job (i.e., receive a salary) and earn some capital income simultaneously. With these examples in mind, let's proceed to the formal definition of compositional inequality.

Formal Definition

If we break down total income into two components, namely capital and labor income, income composition inequality measures the extent to which this income composition is distributed unevenly across the income spectrum. According to this definition, income composition inequality is at its maximum when individuals at the highest and lowest income levels earn exclusively one type of income each, and it is at its minimum when every individual earns an equal combination of the two factors. It is essential to emphasize that the study of compositional inequality can prove valuable in analyzing the joint distribution of any pair of income (or wealth) components, such as net income and taxes, savings and consumption, and financial and non-financial assets, among others.

A high degree of income composition inequality is closely linked to a significant correlation between the functional and personal distribution of income. The underlying idea is simple: when the wealthy individuals in an economy exclusively earn capital income, any increase in the capital income share directly boosts the income of the rich.

From a political economy perspective, the level of income composition inequality can offer insights into the "type of capitalism" present in a given economic system. To elaborate further, according to Milanovic's classification, in a society characterized by maximal inequality in income composition, it can be viewed as a case of classical capitalism. In this scenario, a group of affluent individuals derives their income primarily from capital, while a group of less affluent individuals primarily earns income through labor. Conversely, in a society marked by minimal inequality in income composition, it can be considered a case of new capitalism or a multiple sources of income society.

Analyzing income composition inequality across the income distribution thus enables us to (i) conduct innovative political economy analyses of economic system evolution and (ii) conduct technical assessments of the relationship between the functional and personal distribution of income.

For further details on the methodology I developed for measuring compositional inequality and the Income-Factor Concentration (IFC) Index, please refer to Ranaldi (2022). If you would like to calculate the IFC Index yourself, here you find the stata code and here the R code, this latter prepared by Pedro Salas-Rojo.

Case Studies

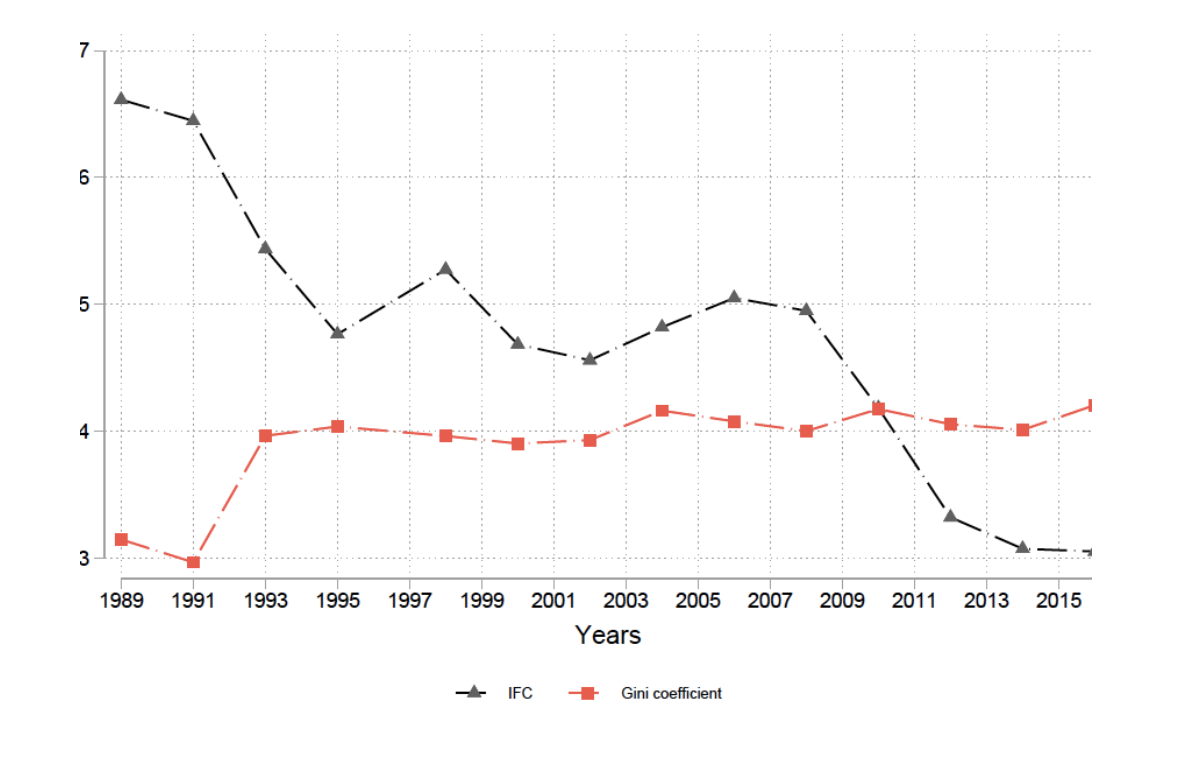

In a recent study with Roberto Iacono, we show that the level of income composition inequality in Italy, as measured by the income-factor concentration (IFC) index, has steadily decreased over the last three decades (see figure below). This result has two implications. First, fluctuations in the total factor shares of income have an increasingly weaker impact on income inequality in Italy. Second, Italy is transitioning towards becoming a society characterized by multiple sources of income. To learn more about the case of Italy, see Iacono and Ranaldi (2023). To learn about the recent dynamics of income composition inequality in the Nordic countries, see Iacono and Palagi (2022). In their research, the authors observe a significant and swift rise in the level of compositional inequality for all the countries examined, particularly in the aftermath of the implementation of Dual Taxation Reforms in the 1990s.

In a recent collaboration with Branko Milanovic, we examine the relationship between various forms of capitalism and their respective levels of income inequality on a quasi-global scale (Ranaldi and Milanovic, 2022). The figure below illustrates our main finding.

In a paper with Bilyana Petrova, we investigate the factors influencing compositional inequality in the European Union. Our research reveals that a greater presence of left-leaning parties in the governing coalition and increased globalization, as measured by trade, capital openness, and foreign direct investment inflows, are associated with reduced income composition inequality. Conversely, higher levels of economic development and a greater share of capital income are linked to increased inequality in income composition (see Petrova and Ranaldi, 2024). Furthermore, in a recent article I present the first estimates of compositional inequality in terms of capital and labor at the global scale in 2000 and 2016 (Ranaldi, 2025). The article shows a significant reduction in global compositional inequality between 2000 and 2016 and argue that this change is equivalent to transitioning from the compositional inequality level of Latin America to that of Canada and the UK. When global compositional inequality is low, an increase in the global capital income share, all else being equal, has limited effects on global inequality dynamics. However, a more equitable distribution of income composition implies that a larger share of the global population is more vulnerable to global financial shocks. The relationship between global and national distributions of capital and labor income for Italy is also outlined in this recent paper. Lastly, in a recent paper with Elisa Palagi (Ranaldi and Palagi, 2022), we investigate compositional inequality in both capital and labor, as well as in saving and consumption across various countries and develop a framework to empirically analyze heterogeneity in macroeconomics.

Normative Aspects

Compositional inequality is a new inequality concept – if it speaks about inequality at all. In discussions about income inequality, it is generally accepted that extremely high inequality is worse than extremely low inequality. Although there is no consensus on the ideal level of income inequality in society—whether it should be zero or slightly more—we can agree that a society where a single individual owns all available resources is undesirable. However, with compositional inequality, the implications are less clear. Is a high level of compositional inequality detrimental or beneficial for society? Is compositional equality inherently desirable? In a recent article, I argue that compositional equality is desirable for at least two reasons. First, from a fairness perspective, given the extreme concentration of wealth—and thus capital income relative to labor income—a reduction in such concentration would lead to a more equitable distribution of asset-derived rewards. Second, from a macroeconomic standpoint, achieving compositional equality would mean that, should the capital share continue to rise due to, for instance, new waves of technological development (among other factors), individuals would not perceive this trend as a threat to their economic well-being, but rather as an opportunity for growth. In fact, under compositional equality (or even negative compositional inequality), an increase in the share of profits relative to overall GDP would imply either equal or pro-poor (under negative compositional inequality) growth along the income distribution. With that said, the reduction in compositional inequality should primarily be achieved either by deconcentrating capital at the top or by increasing capital income at the bottom.